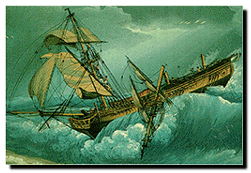

We were schooner-rigged and rakish, with a long and lissome hull,

And we flew the pretty colours of the crossbones and the skull;

We'd a big black Jolly Roger flapping grimly at the fore,

And we sailed the Spanish Water in the happy days of yore.

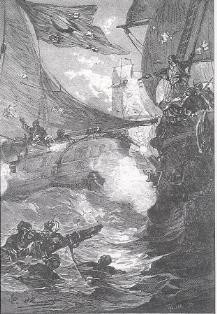

We'd a long brass gun amidships, like a well-conducted ship,

We had each a brace of pistols and a cutlass at the hip;

It's a point which tells against us, and a fact to be deplored,

But we chased the goodly merchant-men and laid their ships aboard.

Then the dead men fouled the scuppers and the wounded filled the chains,

And the paint-work all was spatter dashed with other peoples brains,

She was boarded, she was looted, she was scuttled till she sank.

And the pale survivors left us by the medium of the plank.

O! then it was (while standing by the taffrail on the poop)

We could hear the drowning folk lament the absent chicken coop;

Then, having washed the blood away, we'd little else to do

Than to dance a quiet hornpipe as the old salts taught us to.

O! the fiddle on the fo'c'sle, and the slapping naked soles,

And the genial "Down the middle, Jake, and curtsey when she rolls!"

With the silver seas around us and the pale moon overhead,

And the look-out not a-looking and his pipe-bowl glowing red.

Ah! the pig-tailed, quidding pirates and the pretty pranks we played,

All have since been put a stop to by the naughty Board of Trade;

The schooners and the merry crews are laid away to rest,

A little south the sunset in the islands of the Blest.

A Ballad of John Silver, by John Masefield